Ep. 596 – Dr. Scott Stephens – Summer Rains Provide Major Boost to the Prairies

Chris Jennings: Hey, everybody. Welcome back to the Ducks Limit Podcast. I'm your host, Chris Jennings. Joining me in studio today is my co-host, Dr. Mike Brasher. Mike, how are you?

Mike Brasher: Doing wonderful. It's a Friday. It's Friday morning. It's all good.

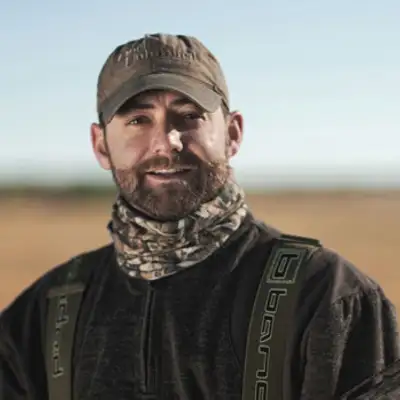

Chris Jennings: It's always good on Friday. And also joining us on the lawn, we have Dr. Scott Stevens. Scott, welcome back.

Scott Stephens: Good to be with you guys. Always good to join you.

Mike Brasher: Where are you joining us from today?

Scott Stephens: This will be my first podcast from Rapid City, South Dakota.

Mike Brasher: There you go, nice. You liking it?

Scott Stephens: I am, yeah, so far. Still got stuff in boxes that, you know, trying to find and figure out and get in place, but yeah.

Mike Brasher: Been in that house for how long now? What, four days? Five days?

Scott Stephens: No, been in, well, had the house for a while, been in the house for a week or so. So, yeah.

Chris Jennings: Just trying to get boots on the ground there in South Dakota, right? I mean, that's what we're looking for.

Mike Brasher: Get your decoys. Those things are all ready. I mean, you know where they are, right? They might still be in boxes, but you have them prioritized.

Scott Stephens: It's not far. Decoys are in a special storage unit.

Chris Jennings: On today's show, we're going to discuss, you know, there's been a lot of discussion, especially throughout early spring. You know, we talked a lot about drought in the prairies. There was some There was some concern, you know, there wasn't a lot of water out there, not a lot of precipitation. Things have changed and so, you know, we wanted to, Mike and I have shared some emails back and forth that I'm sure you've probably seen, but, you know, just kind of discussing some of those changes that are on the prairies and, you know, how that impacts not only this year's you know, waterfowl populations, if it does at all, or, but really just looking forward to, you know, the future, you know, getting that precipitation on the prairies is so important. So, you know, Scott, what are you hearing, especially in Canada, which there it was and still is a little bit of concern, but what are you hearing on the Canadian prairies?

Scott Stephens: Yeah, so I think what we've seen through the spring and into summer has been the same kind of thing on the Canadian prairies as we saw on the US prairies, maybe timing slightly different, where we have gotten some timely rains that have actually changed wetland conditions. That's something that I think it's probably worth talking about is, you know, we could have drought broken. And if you look at drought maps, you know, you might say, oh, precipitation has returned to kind of normal levels. That doesn't always translate into enough water that it ran off, you know, didn't just soak in the ground. and we need the runoff to improve wetland conditions. And, you know, I would also say it's variable, right? When storms roll through in the summertime, you can get three inches of rain in one area and, you know, a sprinkling in another area. So, you know, we're talking about a big geography, but I would say in general, we've got rains that have provided some of that runoff in many locations and have improved wetland conditions. I've been driving a transect from Southern Manitoba to Western South Dakota a few times over the summer. And it was evident to me that, especially as I was in the Eastern Dakotas, it's like, oh, there is water that's now flooded outside of the ring of emergent vegetation that was growing on some seasonal wetlands. So things have improved. For ducks that are attempting to breed this year, I think it will improve probably re-nesting attempts. It will definitely improve the brood survival. And in some of my later trips, I've seen broods out there, all that water and flooded emergent vegetation. We would expect those broods to have higher survival rate. But I think it's probably most important, as you hinted at, Chris, it kind of gets us out of that soil moisture deficit where if we have, you know, more normal precipitation and maybe a timely rain going into the freeze up, then we'll be kind of positioned to have runoff if we get snow and kind of dramatically improve conditions come next year.

Mike Brasher: So, let me see if I interpret this correct. So, Scott Stevens says the drought is over and we're going to have a banner year this fall. Is that what I'm getting?

Scott Stephens: No, you did not. Well, Mike, you know I've been accused of being… What was the quote? I find a dark cloud in every silver lining, I think was one of the pieces of feedback we got on a previous episode.

Mike Brasher: That's right. Bless his heart. Scott Stevens, you can find a dark cloud in every silver lining.

Scott Stephens: Right.

Mike Brasher: So no, I think there is good news. Some people think that. You go online, and maybe this is my problem, I'm looking in the wrong places, right? Chris Jennings would tell me that.

Chris Jennings: Yeah, that's right.

Mike Brasher: He pays too much attention to Facebook. People get so excited about all this news, and it's great to get excited, no doubt about it. But yeah, when it arrived, where, how much, that all is really, really important. It's a really good thing that has happened. We heard and have read from various pilot biologists' reports that a lot of that precipitation came too late to benefit settling patterns for breeding ducks this year. Plus, we started with a low breeding population. We know that for a fact as well, right?

Scott Stephens: That's right. Yeah. Yeah, that's what I was going to say. So here comes my dark cloud that I'm infamous for. Yeah, I would say it came too late. We know… We fully expect we're going to have one of the smaller breeding populations we've seen in a long time, several decades, I would argue. I think we made predictions on the last time I was on. I forget what it was. I said down from before. Mike, you were maybe the ray of optimism there. You were up. And Chris, I think you were the smart guy. You said, I'm not going to guess. I'm going to wait and see what happens.

Chris Jennings: Chris Nielsen Yeah. That was last year. I haven't guessed this year.

Scott Stephens: Yeah. So smallest breeding population, yeah, we have wetland conditions improved kind of later in the breeding season this year, root survival better, maybe a few more re-nests than we would have had if it had stayed dry, but that's going to be kind of marginal impacts on the overall production. I would still say, I would expect the fall flight this fall to be one of the smaller fall flights we've seen in a long time, probably in a lot of waterfowlers' careers. So, you know, have things improved since spring? Yes. You know, should you buy extra cases because you think you're going to go through them? Probably not.

Chris Jennings: You know, what's interesting, and we kind of had this discussion before briefly, I think Mike and I talked about it, but how that late water impacts individual species. You know, we had a discussion where, you know, Gadwall being a little bit later breeders could have benefited a little more, you know, from that late water. And then also, you know, the diving duck species, you know, how does that water impact them? Not only… I'm sure that's, you know, something that, like you said, it's probably some here, some there, you know, not overall, and I don't want you to provide any specifics, but just in general, you know, how does that late water impact each individual species? And we don't have to go through each species, but, you know, where does it come in and where does it play a part?

Scott Stephens: Yeah. Well, maybe I'll start with everyone's favorite, right? The one everybody wants to talk about, mallards. Well, mallards will breed from the very earliest part of the nesting season to the very end. So if mallards probably, where they got the water improvement, probably put in maybe an extra nesting attempt or two if they were unsuccessful. So there might be a little tiny incremental bump in how well mallards did. But you're right, Chris, things like gadwall, the water may have come in time to improve things for them. But again, as Mike said, the pairs were distributed across the landscapes as they were going to be for the year by the time the water arrived. So it wasn't like it got dramatically wetter in, let's say, South Central Saskatchewan and a bunch of birds flocked in there. I don't think we We think that probably happened. Birds were kind of settled where they were going to nest. Now, other species, it's interesting, Chris, you mentioned diving ducks, and most of those, when I think about those, canvasbacks, redheads, nest over water. Actually, that improved water conditions could have created challenges for them if they had the nest bowl in place and then we got water rising. There could have been some flooding impacts. I haven't heard reports of that, but based on the change in water levels that I saw in some seasonal wetlands, we could have seen some water rise in semi-permanent wetlands that they'd be nesting in.

Mike Brasher: There's that dark cloud.

Scott Stephens: That's right. Thank you.

Mike Brasher: That's right. Thank you. Along the lines of a potential dark cloud, another one I'm going to throw to you. One of the other things that we've seen in addition to above average precipitation across a good chunk of the Canadian and U.S. prairies this year is some cooler temperatures. I think temperatures have run a few degrees below normal, and I was reading the Canada summary, weather summary for the month of June, and I think it may have been in Alberta, and I don't know how widespread it was, but there was a mid-June frost. What does that do from a duckling survival standpoint? How vulnerable are they once they get to June if you have a frost, I guess, regardless of when it is?

Scott Stephens: Yeah. It will really depend on the species and the timing of when they hatched. We know that ducklings are the most vulnerable in the first two weeks that they're hatched and out there, right? So if you get, typically the recipe is cool, wet temperatures. During that time, obviously the hen is with them and doing what we would call brooding. She's trying to keep them together and keep them warm because they're just not good at thermal regulating for that first couple of weeks. Now, so if that coolness came after many of the ducklings that had hatched were a couple of weeks old, probably fine. Nests, it won't be a problem. The female, if she's incubating, she'll keep those eggs warm. Frost wouldn't be a problem. And if she was laying, those eggs are pretty cold hardy. So, I wouldn't be too worried about one early morning of frost having a big impact on production. Do you want to take a break?

Chris Jennings: Yeah, yeah, we'll take a break real quick. We'll come right back.

Mike Brasher: You wore out? No, we're gonna take a break. We're gonna come back. We got some more stuff. I want to talk about… Where did that come from? I want to talk about some boreal forest fires and things of that nature.

Chris Jennings: I was gonna ask that as well.

Mike Brasher: We'll take a break. Go ahead. Take us to the break, Chris. Alright, we're gonna take a break.

Chris Jennings: All right, welcome back from the break. We have Dr. Scott Stevens, who is currently laughing into his microphone. We also have my co-host, Dr. Mike Brasher here, and we're talking about habitat conditions across the prairies. But before we went into the break, Mike brought up the fact that he wanted to ask some questions about the boreal and the importance of the boreal. It's just absolutely significant for breeding waterfowl, but the conditions up there, Constantly, they're probably a little more stable, I would say, than the prairies, actually. But there are some different things that you guys look at and kind of take into account when talking about breeding waterfowl. So how is the boreal and what are the habitat conditions up there? What are you hearing? Any feedback you have from that region?

Scott Stephens: Yeah, so what I've heard so far, I mean, when we get to this time of the year, you're always concerned about fire up there. There were definitely some fires earlier that caused some evacuations of some of the remote communities. I have not heard much about that recently, so I'm assuming that maybe some of the precipitation that we had roll through kind of western Canada in the prairies also provided some rain across that boreal forest region too. So that's good because the fires are not great, especially for the communities that get disrupted and they get shipped somewhere else. And yeah, just a big hassle for sure. But habitat conditions, I would characterize as pretty normal or average. And you're right, Chris, we don't go through the big fluctuations that we see in the prairies. So there's kind of a normal range of variation, but those systems tend to be more stable, more kind of permanent, stable water in those systems in the boreal. So I think we'd have pretty normal breeding conditions up there.

Mike Brasher: Scott, that was an area where I think this year, coming into the spring, we were particularly worried because it was abnormally dry in the boreal, which is unusual just to begin with. As we've talked about here, typically a bit more stable, but we saw extreme drought across good portions of the western boreal forest, and there were people that were worried about, a lot of people worried about, like another record fire season. And so I, before we got on here, I pulled up the, I think it's the Canadian, the National Wildland Fire Situation Report, just to kind of get a handle on an understanding of what that current situation is. And there are fewer fires affecting fewer acres this year to date, you know, as of compared to the average. I don't have the data for last year to do that comparison, but I can just report here that as of July 3rd, the area affected by fire, this may be active fire is what this says, 830,000 hectares. That's incredible. You know, we talk a lot about it's difficult to get people to appreciate the scale of the prairie pothole region. I think it's even more difficult to get people to appreciate the scale of the western boreal forest. I certainly don't have an appreciation for it, but when you start thinking of talking about 800,000 hectares affected by, according to this, active fires across Canada, that's incredible. The average to date is, like, to this point of the summer, or of the year, is 1.4 million, roughly. So, it's below average in terms of the acres or the hectares affected by fire right now. Fewer fires than average, fewer less area affected. So from that standpoint, yeah, it was not as bad, has not yet been as bad from a total standpoint as many people were expecting.

Scott Stephens: Yeah, I mean, the best way I have found to try and think about the context of the scale of the Western boreal is, you know, it was a number of years ago, I took a trip to Alaska and left Minneapolis and flew to Anchorage and you fly most of that time, you know, for hours and hours over boreal forest. So, You know, you think about just the massive area as you kind of look down and the number of hours that you're flying, you know, at 30,000 feet cruising at what, you know, 500 miles an hour or something. So, it's a massive area. So, yeah, even though 800,000 hectares sounds like a big area, it sounds like that's less than the normal amount of fires going on. And it's a system that has always had forest fires, probably at a higher frequency as we've had some of the impacts of a changing climate impacting that area like it has everywhere else. But yeah, it's not like… Sometimes I think we get in the mode of, fires are totally abnormal and completely destructive and all of the ducks and all of the critters that use that ecosystem as home, they evolved being accustomed to dealing with periodic fires and having to move around the landscape and those kind of things.

Mike Brasher: Chris, I guess a bigger picture look here. Eastern Canada is, based on kind of what I'm seeing from the drought map, is in pretty good shape. I think they've had some precipitation across most of the eastern provinces, so pretty good shape there. I believe there are some dry conditions as you get over along the coast there of Atlantic Canada. There are still some dry areas in portions of the prairies. You know, it hasn't been universal good above-average precipitation there across the prairies. I think farther west into Saskatchewan and southern Alberta, still kind of dry, but did get some relief, definitely. So, trending in the right direction pretty much across the entire Canadian prairies and the US prairies as well as looking at a map here a moment ago percent of precipitation since mid March, you've got portions of eastern North Dakota that are like 200% of average and. Minnesota, also southern Minnesota, just been drenched week after week it seems like. So pretty good wetland conditions right now across a good chunk of that important area. The other thing that I was looking at from a drought standpoint as you look down into compared to last year this time, not as much drought in the central Great Plains or the Midwest. It's starting to get a little dry down here in the south. Um, not as dry out in California right now. Um, so I think I'm looking at some drought along the east coast, but, uh, but overall it's better kind of, I guess, coast to coast than it was this time last year from a precipitation standpoint. Anything to add to that, Scott?

Scott Stephens: Well, what I was going to add when you talked about some of those areas that had received lots of precipitation, what I can report on confidently is that before I left Manitoba with all that precipitation, we have a bumper crop of mosquitoes going on in Manitoba this year with it being wet and pretty frequent rains. And I know I got a report from one of my friends just recently, it's like, oh Lee, you've missed more rain since you left and boy, do we have mosquitoes. And it's like, yeah, I'll bet.

Mike Brasher: I actually want to correct myself a little bit. It appears we do have some drying conditions in Montana. before anybody sort of chimes in and says, we don't know what you're talking about. So yeah, a little bit of drought showing up in Montana, portions of the Intermountain West out there. So what else we got, Chris?

Chris Jennings: You know, Scott, we had John Pullman on a couple weeks ago, and he kind of brought a little bit of, you know, he didn't have a really in-depth description of wetland conditions in South Dakota, but we really, I mean, you just touched on it, Mike, the U.S. side of things. We really haven't discussed that, but I mean, the U.S. prairie seems to be in pretty good shape right now. I mean, are you seeing that, you know, as you're traveling around through the Dakotas?

Scott Stephens: Yeah, I would say we definitely saw improvements. You know, the last trip I was down, you could tell that there were seasonal wetlands that I had driven by that had a little bit of water in them. And when I came came by recently, they were probably flooded five or six feet outside of that ring of emergent vegetation. Yeah, and as I had driven a few weeks ago from Rapid City to Sioux Falls, so once I crossed the river, I get in pothole country, and there was pretty good water as I kind of drove east there. You know, that was encouraging. Chris, as you mentioned, John's name. I was on with John, I think, providing some information for a magazine article, and he had to give me a bad time, because he said you characterized him as the second most popular podcast guest in South Dakota these days.

Chris Jennings: I did. I told him he got bumped. I was like, you got bumped, man. You're popular, but now Scott lives in South Dakota, so sorry. What do you have to say about that? John's a very humble man. Very gracious.

Mike Brasher: Yes, not gonna not gonna challenge Scott to a duel sounds like he was going to Yeah, he brought it up when we talked but that's okay, where do y'all live relative to one another how far apart you

Scott Stephens: Yeah, we decided he could be the most popular guy in East River, South Dakota, and I'm West of the river. So yeah, we, we sorted that out.

Mike Brasher: Do we need to get a remote DU podcast studio up there? Where, how far apart are y'all and y'all meet in the middle?

Chris Jennings: I think they're pretty good ways.

Scott Stephens: Yeah, we're probably, we're probably five hours apart. So yeah, maybe, maybe if we could have one, you know, in the middle, like, uh, I don't know, pier or something right there on Lake Oahe, that, that would be okay. We could, you know, maybe catch some fish, do a podcast.

Mike Brasher: Yeah, you'd need some help setting up the studio and trying it out.

Chris Jennings: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, absolutely. Go test it out, test out South Dakota. Hey, Scott, one more thing, and this is just me thinking, you know, one of the most interesting regions, we talk about the prairies a lot, we talk about the boreal, but that transition area in the parklands, It is an extremely important region for breeding waterfowl. Are you hearing anything from that Parklands region that's just kind of talking about, you know, any conditions up there? And again, it's one of those areas that doesn't quite have the fluctuations of, you know, conditions that the prairies have. A little more stable, kind of like the boreal, but are you hearing anything from the Parklands?

Scott Stephens: Yeah, I think at least in the sort of eastern half of Saskatchewan and definitely in Manitoba, those parkland areas have gotten some of that rain. And that's common, because as you described, Chris, if you looked at average precipitation, it's more stable and higher than it would be further south in true prairie areas. So I think those areas are shaping up pretty well. conditions may be setting up where next year, maybe we have really good production because some of those areas may have dried out as things got dry. And then with the vegetation growing back, we'll have that flush of productivity that is probably less common in the park lands. But when it happens, it will be the same kind of boom in productivity from a aquatic insect standpoint. The ducks take advantage and it sort of translates all the way up the food chain.

Chris Jennings: No, that's awesome. And then, Mike, did you have anything to add? I do. All right. Have at it.

Mike Brasher: I have a… Magnum? I'm wearing sort of a flowery Hawaiian t-shirt. Not a… Hawaiian shirts, not t-shirt. And so they're kind of… They don't know what to do with this right now.

Scott Stephens: We likened them to the old school Magnum PI, the Tom Selleck version, not that newfangled Gen Z. Except I can't grow a mustache.

Mike Brasher: Well, I could, but you wouldn't want to see it. So, what was I going to ask you? Yeah, okay. Habitat conditions, prairie wetland conditions have improved compared to last year, this time of the summer. Put yourself in the mind of a hunter who's sort of thinking about heading north, either to the U.S. prairies or Canadian prairies. What's that going to look like? How's it going to be different from, let's say, the last two years? And then, what does that mean for the strategies that a person might want to think about? What should they anticipate? What should their expectations be?

Scott Stephens: Yeah, well, this isn't really a hypothetical for me. That's why I asked the question. Yeah, I have been thinking about that. And for me, at least, it starts with, if you have traditional areas that you go to, you'll want to check to see if wetland conditions have improved in those areas where you normally head, right? You know, because as we talked about, it'll be spotty. You know, there will be areas that got more of that rain, had more of that runoff, and conditions can be dramatically improved. And there could be areas that are maybe not changed much from dry conditions last year. So that's where I start is, you know, you'll want to check the local conditions in the area that you plan to go. But I think the good news is that with those improvement in conditions, there's likely some place that you could find if your strategy is flexible and you want to roam around and kind of find the water. I'm sure you will find the ducks, find the geese, hitting dry fields, using wetlands, all of those things. So yeah, for me, it starts with figuring out, okay, where did we see the improvement? Where are wetland conditions good that are going to hold birds?

Mike Brasher: Should they anticipate a lower fuel budget this year, not having to drive as far to find water?

Scott Stephens: Generally, I would say, yeah, because there should be more water on the landscape. That will spread birds out across broader areas. For me, as I was hunting the Canadian prairies last fall, it was tough. I drove 12 hours from Southern Manitoba to Western Saskatchewan and there was no water there. And we ended up coming back almost to the Manitoba border before we found decent water and found some huntable numbers of ducks. So yeah, the fuel budget was high last year. Hopefully that'll be a little bit lower this year. But it'll be, I would say, do your homework, check with local folks, you know, pull up the maps that you can online to look at cumulative precipitation over the past two or three months here. And all those resources will help you kind of hone in on areas where your odds are going to be best of finding birds and find an opportunity.

Chris Jennings: Yeah, see, I was kind of thinking just the opposite, that your fuel budget's going to go up because with water across the landscape, the birds will be a little more spread out.

Mike Brasher: So you're going to have to find… Especially with the anticipated smaller fall flight from, let's say… There you go, yeah.

Scott Stephens: Yeah, but I mean… Yeah, I think people will be able to find birds. I guess it depends on what your threshold is, Chris, for a huntable number, right? Yeah, that's right. If you're looking for the massive feed, yeah, you may still have to look a while because they're going to be spread out. But yeah, there will be huntable numbers of ducks in a lot of areas would be my assessment.

Mike Brasher: What about decoy strategies? Are you going to be packing your skinny teal plus your florals?

Chris Jennings: I was going to say more silhouette blue wings.

Mike Brasher: Because, see, you're not going to have as much mudflat, though. So the skinny teal were a little decoy that you developed a few years ago during drought situations because you had so much mudflat. What's this do to you? You got water out beyond the rim of the cattail. What do you do with skinny teal? They're going to get lost in the vegetation.

Scott Stephens: No, I would say it doesn't change the strategy much because at least my recipe for teal is they want water about four or five inches deep anyway, regardless of condition. So they'll be looking for that. Yeah, you may be setting up those decoys between the emergent vegetation and the shoreline rather than inside that emergent vegetation. But yeah, for teal at least…

Mike Brasher: affix a longer stake to it or something if the water's deeper or something.

Scott Stephens: You could do crazy stuff like that, yeah, but if it's just too deep in the situation you're in, I just leave those in the bag and throw out the floaters.

Chris Jennings: And as long as you add maybe another half dozen coyote decoys. Oh, dude, I was gonna go there. So you could add them on the other, the wetland, the surrounding wetlands. The song dog. That's right. The song dog.

Mike Brasher: That's right. How does the change in wetland condition affect the song dog deployment?

Scott Stephens: I don't think it probably does. It's, it's, it's still a strategy that, you know, primarily a field hunting strategy. If you've got a big field that you want to keep the geese out of and angled over toward your spread, you're going to use that in, in the Dakotas.

Mike Brasher: Are you afraid people are going to laugh you out of there? Cause you know, there's going to be more eyes on you in the Dakotas.

Scott Stephens: Hey, I'm never afraid to be laughed at. So, you know, we'll see, we'll see what happens if it's effective and people think it's funny. I was going to say, it's probably going to get shot out there. It could get shot. Yeah. Like the one that I have is like a, you know, it's like a silhouette. It's a Montana decoy, you know, made out of fabric and sort of pops up and just 2D, but yeah. So. It might have a hole in it if it gets shot, but it won't be busted into pieces or anything. But yeah, you want to be careful with stuff like that.

Chris Jennings: Nice. Well, before we get out of here… I have one more serious thing, but you go. Oh yeah, I had a serious thing too. So, are either of you hearing anything? It's one thing we haven't really touched on, is kind of the Arctic and goose populations. Are you guys hearing anything from snow geese, white fronts, all those Arctic breeding birds?

Scott Stephens: I have I have not heard a report from the folks who are knowledgeable in those but but what I would say is always for me. The litmus test is, if you look at the snow cover map around the early part of June, that is usually tells you a lot about what what. the reproductive success is going to be like for those geese. So if they are generally snow free by early June, then that bodes well for production. And if there's still snow there by early June, that can be problematic and production may be less. But I have not looked at those maps and doesn't sound like you did either, Mike.

Mike Brasher: I did not, and I'm not even going to attempt to find those because I probably would not be able to here on short notice. Would you have to get somebody else on to talk about that? Yeah, for sure. So, speaking of that, someone to talk about all kinds of interesting things related to waterfowl, ducks, geese, population size, and so forth. Folks might remember the past two years we've had our Waterfowl Season Outlook live stream in the immediate wake of the release of the Breeding Population Survey. And we're going to do that again. And we've got some exciting news to share in that our very own Dr. Scott Stevens is going to be joining us in person for that event. We're going to have a panel right now. The tentative lineup is going to be Scott, it's going to be Dr. Matt, Mr. Dark Cloud, Dr. Matt Dyson from DU Canada, he joined us last year, might have joined us the last two years, I can't recall, it all runs together. No, he didn't join us two years ago, I don't think.

Scott Stephens: I think he did virtually two years ago.

Mike Brasher: Oh, that's right, that's what it was. And then we are efforting Dr. Dan Collins from out in the Western region, and then we're going to have a number of other panelists. Efforting, what does that mean? There's an old Dan Patrick thing. He used to say that all the time on his Dan Patrick radio show, Efforting. I think Phil was his, like, producer or something. Efforting. So, it means we're trying to make that happen.

Scott Stephens: That's a new one on me. I had not heard that.

Mike Brasher: That's an interesting one. Oh, he's stuck in my mind. Okay, so we're Efforting, Dr. Dan Smith, and we are also going to be lining up sort of a panel, remote panel of, I don't know, half a dozen or more individuals that are going to be able to pop in and give us some updates from different parts of the country, maybe somebody from the Klamath, maybe somebody from the Great Lakes. We're going to try to get somebody from the Canadian Wildlife Service or somebody else to be positioned to talk about the goose numbers and what we saw there. Also, we have received tentative confirmation that we're going to have Phil Thorpe, one of the longest-tenured Fish and Wildlife Service pilot biologists joining us remotely. He's flown the transects and strata there in southern Saskatchewan for a number of years, and so he's going to kind of give us a first-hand account of some of that. So we're trying to make this more about, like, a lot of information. We're going to field questions from the participants. Keep your eyes and ears peeled for that. We'll share more details as it gets closer. Tentative date right now is August 26th. That'll be an evening livestream thing, so. Cool. Yeah, good stuff.

Chris Jennings: Exciting stuff. Well, Scott, this has been great. Appreciate you joining us today.

Mike Brasher: I don't know if I, should I wear this shirt?

Chris Jennings: I would not.

Mike Brasher: I would not.

Chris Jennings: I would not. We'll put it to a vote. Yeah, put it to a vote.

Scott Stephens: We'll get some fashion consultants in before we come out there.

Chris Jennings: He needs it. Back to you, Chris. Yeah. All right. Well, Scott, I appreciate you joining us today. Information you've provided is always fantastic. You know, it's something that, you know, waterfowlers definitely are paying attention to the precipitation, especially going into the spring or going to coming into summer. Even we were so dry that I think we really, there was a lot more eyes on it than had been in the past. And it sounds like, you know, you, you provided some pretty good positive information. for all of us to take away. So, it's an eternal optimist as a waterfowl hunter. It's always good to get a little good news. So, I appreciate that.

Mike Brasher: Yeah. Thank you, Scott. I appreciate it as well.

Chris Jennings: I'd like to thank our guest, Dr. Scott Stephens, for coming on today and providing Habitat Update. I'd like to thank my co-host, Dr. Mike Brasher, for wearing that ugly shirt. I'd like to thank Chris Isaac, our producer, for putting the show together and getting it out to you. And I'd like to thank you, the listener, for joining us on D Podcast and supporting wetlands conservation. It's not an ugly shirt. It's an ugly shirt. It better be comfortable.